Hidden Treasure

A Josie Prescott Antiques Mystery

Jane K. Cleland

READ THE FIRST TWO CHAPTERS!

CHAPTER ONE

I was feeling fine, better than fine. I was riding high. My TV show, Josie’s Antiques, had been renewed for a fifth season, and Ty and I had just closed on the house of my dreams. What a way to start a Monday.

I was back in my office after seeing Ty off for a can’t-change-the-date, hush-hush training exercise in Vermont, part of his job for Homeland Security. I was itchy to be up and doing. I couldn’t stop smiling.

My phone buzzed. It was Cara, Prescott’s newly promoted office manager. “A Celia Akins is here, Josie. She insists on seeing you right away.” Cara lowered her voice. “She’s the niece of the person you and Ty bought the house from. She says there’s a problem.”

We’d only owned the house for an hour—how could there be a problem? “What kind of problem?”

“She didn’t say.”

I could hear the tension in Cara’s voice.

“All right. Bring her up.”

When I heard footsteps on the spiral staircase that led to my private office on the mezzanine level, I dislodged Hank, Prescott’s Maine Coon cat, from my lap so I could stand. He made a frustrated, guttural whine. Hank had attitude. I reached down to pat his furry little head, and he sauntered away.

Celia Akins was short and stocky with curly dirt-brown hair, a double chin, and thin lips. At a guess, she was around forty.

I thanked Cara and said hello to Celia as I walked toward the seating area. I stood in front of a yellow brocade Queen Anne wing chair.

Celia murmured hello as she sank onto the matching love seat. Her ruddy cheeks were flushed, and she seemed to have trouble meeting my eyes.

“Thank you for seeing me without an appointment.”

“I’m glad I was here.”

“I feel terrible talking about family matters to a stranger, but we need your help. My sister, Stacy, and I. For our Aunt Maudie.” She lowered her eyes to her hands, gripped tightly together in her lap, then raised them to look me dead in the eye. “You bought my Aunt Maudie’s house.”

“My husband and I did, yes.”

“Stacy and I are Aunt Maudie’s only living relatives. We’re protective of her. We love her.”

She seemed to expect a response. “She’s a lucky woman.”

She licked her lips, then lowered her eyes again. Her discomfort was making me uncomfortable.

She raised her eyes. “I made a mistake. This is all my fault.”

“I’m sorry, but I don’t understand.”

“I didn’t check everything before the movers came. Stacy lives in New York, so naturally it was my responsibility because I’m local. I didn’t do a good enough job, and now Aunt Maudie is missing a trunk.”

“A trunk?”

“She doesn’t remember when she saw it last.” Celia paused again, pressing her lips together. She was in the throes of some strong emotion, but I couldn’t tell what. “It’s perfectly understandable that she’s confused and forgetful. She lived in that house for forty-five years, ever since she married Uncle Eli, and Uncle Eli was born there. The house had been in the Wilson family for more than a hundred and fifty years. After all those years, and alone . . .”

“Moving can be a nightmare.”

“Exactly, and it’s extra awful for someone forced to sort through generations of accumulation not their own. Aunt Maudie can’t remember seeing the movers load it. The movers say they took everything they were supposed to and delivered it all as instructed, some furniture to me and all the rest to Aunt Maudie. Stacy thinks it got thrown out by mistake when Aunt Maudie brought in the junk removal company, but there’s no way to tell. They track loads by weight, not items. Our only hope is that it was somehow missed during the move.”

“I wish I could help, but I don’t think I can. I did a walk-through this morning before the closing. The house is empty.”

“I know losing a trunk isn’t like losing a deck of cards, but it’s possible. The attic is big and dark. So is the cellar. Maybe it’s behind the boiler, and just got missed. I was hoping you’d let me take a look.”

I felt a twinge of hesitation, an innate territorial objection, but only a twinge. I knew how wrenching it was to lose cherished objects.

I swallowed my qualms. “Of course.”

Celia stood. “Can we go now?”

I agreed, and she called her husband, Doug, and asked him to meet us there.

Fifteen minutes later, I rolled to a stop on the sandy shoulder behind Celia’s silver Toyota RAV4. Doug, she said, should arrive in a minute or two.

I led the way through the black metal gate and along the flagstone walkway to the porch, then leaned against one of the round columns and settled in to wait for Doug. Tall tiger lilies and white heirloom bearded irises lined the walkway. I could hear the waves breaking as they rolled to shore, but I couldn’t see them. They landed with a soothing, hypnotic rhythm, not a crash or a roar, more like a rumble. The briny scent of the ocean glided in on a soft breeze. The sky was bright blue and cloudless. It was a picture-perfect day, a day for new beginnings, one of God’s days, my mother would have said.

“Thank you for this,” Celia said. “I know it’s an inconvenience.”

Given her somber mood, I didn’t want to tell her that despite my slight hesitation, I was thrilled to have an excuse to walk through my new house, my home, again.

Doug drove up in an old green Subaru Outback. He looked to be around the same age as his wife, early forties. He was tall and skinny with big ears that stuck out from his head and graying hair close cut. He wore a short-sleeved blue shirt with too-big jeans and work boots.

When he reached the porch, he patted Celia’s arm, then turned toward me. “We appreciate this.”

“Of course.”

I used my key, and the three of us stepped into the entryway. The house, which was located on a secluded triple lot abutting the north end of Rocky Point Beach, featured a wraparound porch, hexagonal rooms, and fanciful detailing. In our coastal New Hampshire community, it was called the Gingerbread House. I knew from our real estate broker that Mrs. Wilson had moved to the independent wing of Belle Vista, an assisted living facility, three months earlier, which explained the dank odor. Sunlight dappled the old oak flooring and flecked the mahogany doors and window frames with golden glints. On the walls, squares and rectangles in a darker shade than the rest of the paint, ochre instead of tan, indicated where artwork had hung.

“You mentioned that the trunk might be in the attic or the cellar,” I said. “Shall we begin at the top?”

We climbed the main staircase, a grand affair that included a spacious landing halfway up. I paused for a moment at the oversized windows to look out over the Atlantic. Sun-sparked glitter danced along the midnight-blue surface. From the landing, we trooped up the rest of the stairs to the third floor. The attic, located on what was the equivalent of the fourth floor, was accessed through a bedroom at the front.

It was stuffy under the eaves. Three dangling low-watt lightbulbs provided the bulk of the light, helped along by sunlight that trickled in from porthole-like windows mounted high on the north and south walls. I stood in the center watching Doug and Celia search the entire area. With Doug holding an old flashlight he’d brought along, Celia squatted to peer behind joists and crossbeams. Other than dust motes, the place was bare.

“The cellar next?” I asked.

We walked back down, this time using the back stairs. We passed through the butler’s pantry and took the last flight down.

The basement was about ten degrees cooler than the ground floor. Its concrete walls and floor had been painted industrial gray a long time ago. Except for three rows of empty wooden shelving, a small apartment built into the back corner, and a separate room for the boiler, the space was wide open.

Celia walked directly to the boiler room. I stood at the threshold, watching Doug aim his flashlight while Celia examined the space between the boiler and the wall.

“Nothing,” she said. She walked back into the open area, stopped in the center, and turned around. Her lower lip quivered. “The trunk’s not here.”

Doug put his arm around her. “It’s all right.”

“No, it’s not,” she whispered, “and it’s all my fault.”

“No, no,” Doug said.

“I knew Aunt Maudie was getting forgetful. I should have done more.” “You did the best you could.”

After a few seconds, I asked, “Did you want to walk through the rest of the house?”

“There’s no point,” Celia said. “There’s no place left to look.”

Celia walked out, her feet dragging. Doug thanked me again and handed me a slip of paper with his and Celia’s phone numbers written in a spidery scrawl. I stood on the porch watching as they trudged down the path. They disappeared behind the screen of sumac and scrub oak that shielded our property from Ocean Avenue.

I leaned against the column, breathing in the salt-steeped air.

I hoped Celia would come to realize that anyone can lose anything, whether it’s a pack of cards or an entire trunk. Maybe then she could forgive herself.

CHAPTER TWO

The next morning, Tuesday, I arrived at the Gingerbread House just before eight to supervise two of my employees packing up the crystal chandelier from the dining room. Ty and I planned on putting it back after the renovation, and I was champing at the bit to appraise it and learn its history. The removal was a delicate and exacting process, and when the chandelier was safely crated and in the van, I breathed a to-my-toes sigh of relief.

During our early morning phone call, Ty told me that his training exercise had not met expectations, probably a euphemism for a complete bust, so he had to revamp the procedure. If there was another misstep, he’d need to go to Washington to discuss ways and means with his boss.

The demolition-planning phase of our house renovation was scheduled to begin tomorrow afternoon, and Ty was concerned that he wouldn’t be there for our last-look and measuring session. I knew I could measure the rooms and sketch out the various nooks and juts on my own, but I’d been looking forward to planning paint colors and furniture purchases with Ty as we walked the house for the last time before the reno began. I swallowed a pang of disappointment and assured him that I would be fine. But four eyes were always better than two, and measuring is far easier when someone else holds the other end of the tape measure, so I called Tom Hill, who’d been Mrs. Wilson’s live-in handyman-cum-gardener, and who’d agreed to continue maintaining the grounds for us through the renovation. Luckily, Tom was available, and glad for the work.

While I waited for him, I got a stepstool and toolbox from my car trunk and brought them inside, then straddled the porch railing, enjoying the warmth. Tom appeared at the gate. He was tall and fit, close to thirty, with short sandy hair and regular features. He’d spent eight years in the army, and it showed in his posture and demeanor. He waved to me, a half-salute, then turned back to the road and said something I couldn’t hear to someone I couldn’t see. When he finished, he strode down the path toward me, smiling.

“Top of the mornin’ to ya,” he said.

“And to you. Thanks for helping me out on such short notice.”

“Your timing was perfect. Julie’s car died last night, so she’s using my pickup. You called just as she was getting ready to head to school, so she was able to drop me on her way.”

I’d met Tom’s girlfriend, Julie Simond, a couple of times when Ty and I stopped by the Gingerbread House. We’d found Tom fussing around the garden and Julie fussing around Tom. She was twenty-three, hailed from Plainview, a blue-collar town close to the interstate, and was studying nursing at Hitchens University.

“Bummer.”

“It comes at a bad time, that’s for sure.”

“I can give you a ride home when we’re done here.”

“Thanks. Julie only has one class today, and her shift at the diner isn’t until later, so we should be okay.”

I led the way inside. “We can leave the toolbox here. I’ll bring the stepstool with me—I’m short.”

“You’re petite.”

“Ha! A rose by any other name . . .” I picked up the stepstool. “I think dividing up to check the rooms, then measuring together will be the fastest approach.”

“Sounds good. Should we skip the attic and cellar?” Tom asked.

“Celia said they were completely empty.”

“You spoke to her?”

“This morning. I was installing some track lighting for one of Celia’s neighbors—she was nice enough to recommend me. Anyway, Celia’s pretty bummed the trunk is missing, and from what I hear, this trunk contains some valuable stuff.

“It’s horrible to lose things. You feel so powerless.”

“Like I told her, you do what you can, and that’s all you can do. So, what’s our plan?”

“I think skipping the attic and basement makes sense. You can start on the north end of the third floor and I’ll start on the south end, and we’ll meet in the middle.” I explained that my walk-through with Ty before closing had been just a quick look-see, and now I wanted us to look inside each drawer and cubbyhole of the bedroom’s built-in wardrobes and deep closets, under anything that wasn’t flush to the floor, and on or over anywhere else where something might be found.

Forty-five minutes later, having examined every inch of every flat surface in three rooms, about the halfway mark, I walked to the middle of the corridor that ran the length of the house. I let my eyes wander to the ornate crown molding, the wainscoting, and the large scrolled leaf-edged ceiling rose, fine details Ty and I wanted to keep, along with the wide oak plank flooring, which had been burnished to a luxuriant red-gold through more than a century of care and polish. The silence was omnipresent, broken only by an occasional creak as the old house settled and a hushed sense of the ocean’s movement. The serenity was relaxing, like nestling into a reading nook with a favorite book. After a moment, I called for Tom.

He stepped over the threshold of the bedroom nearest me, holding a rusty wrench in front of him like a conductor holding a baton.

“Guess what I found?”

I tapped my chin with an index finger, pretending to think. “A rusty wrench.”

Tom grinned. “How’d you guess?”

“I’m known for my sharp-as-a-tack deductive reasoning. Where did you find it?”

“Under the radiator.”

“I bet whatever plumber did the repair still wonders what happened to his wrench.”

“He probably blamed his apprentice for stealing it.”

“Oh, I hope not.” I laughed. “I bet the plumber is the sort of fellow who is terrific at his job, focused and intuitive, but when he’s not working, he’s a little scatterbrained. He blames himself.” I smiled.

“You can tell a lot about people by how they fill in the blanks.”

“I’m cynical. You’re optimistic.”

“I don’t think of you as cynical.”

“Of course you don’t. An optimist wouldn’t.”

I laughed again.

“This rusty wrench is my total take. How about you?”

“Not even a rusty wrench.” I told him where I left off and asked him to finish up. “When you’re done, how about if you take the second floor? I’ll start in on the ground floor.”

“Sounds good.”

Downstairs, I made my way to the music room, so named because of the vignette-style classical musical notations on the wallpaper. A built-in bookcase was bare. So was the firewood storage cubbyhole next to the fireplace in the living room. The dining room was huge, perfect for big get-togethers, a thought that always made me smile.

As the only child of only children, I had the tiniest of families—only one cousin, and she lived in England. Ty was also an only child, and his parents hadn’t been close to their siblings, so while he had a decent-sized extended family, he barely knew them.

Thanksgiving dinner for two at a table designed to seat twenty would be fine, but I thought it would be more fun to fill it up. I began preparing a mental list of who we could invite to join us.

All the bookcases in the study were open and empty. The powder room didn’t even have a medicine cabinet I could look in. I used my stepstool in the kitchen to confirm that all the upper cabinets were empty. So were the bottom cabinets and drawers. The last space to check was the butler’s pantry, one of my favorite parts of the house.

At twelve by fifteen feet, it was bigger than most bedrooms and featured a wealth of storage and fifteen-foot ceilings, like the rest of the house. In addition to the two back stairway doors—one leading up to the second floor and the other leading down to the basement—a swinging door accessed the kitchen, and a side door opened onto a flagstone pathway and a kitchen garden. There was a big window in the side door, but not much sunlight made it inside because of a deep overhang, a nice feature when collecting herbs in the rain, but of limited help on a sunny day when you’re trying to see into corners. Floor-to-ceiling custom-built storage units covered all available wall space.

As I reached to open a drawer in the built-in closest to the outside door, I heard a steady, repetitive click-clack. Someone wearing high heels was walking purposefully toward me. Startled, I gasped.

“Hello?” a woman called. “Ms. Prescott? Are you here?”

I took a few seconds to regain my composure, then pushed through the swinging kitchen door. Three paces in, I could see the entryway. An attractive woman I’d never seen stood five feet from the front door.

“I’m Josie Prescott,” I said.

She smiled. “I recognize you from your TV show. I’m a huge fan. I’m Stacy Collins, Maudie Wilson’s niece, Celia’s sister.”

She must have read the astonishment on my face as I glanced at the front door because she said, “Apparently, the bell is broken.” She smiled. “I used my key.”

“Your key.”

“I went to your office, and they told me you weren’t in. I thought maybe you were here, and you are! I’m hoping you have a moment to talk.”

Stacy was a few years younger than Celia, thirty-five or thirty-six, perhaps, and cut from entirely different cloth. Whereas Celia was comfortably proportioned and dressed with country simplicity, Stacy was svelte, every inch a city girl who dressed to impress. Her salmon sleeveless raw silk sheath fit her as if it had been made for her, and maybe it had. Her blond hair was cut in a striking wedge. She wore ivory open-toed pumps with three-inch heels, two inches higher than most women in Rocky Point wore.

I slipped past her to the front door and opened it. “Why don’t we step onto the porch?”

She hesitated, probably worried I was giving her the bum’s rush, then walked outside. I patted my back pocket to confirm I had my key before following her out and shutting the door.

I leaned against the porch railing. “What can I do for you?”

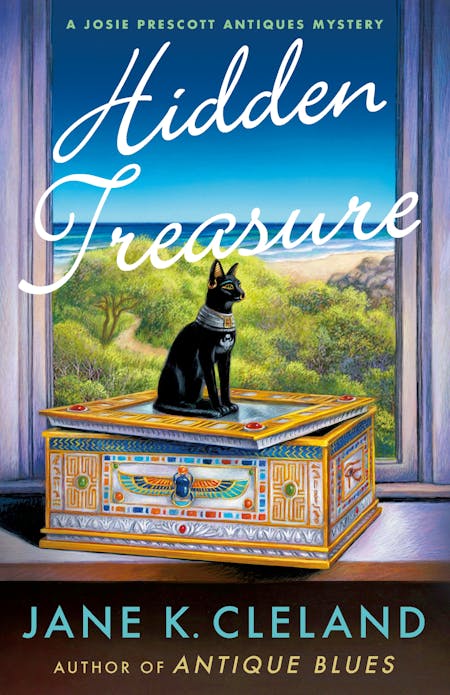

She tried to smile, realized it wasn’t working, and let it go. “This is painful for me to talk about. I wish it wasn’t necessary, but I guess there’s no way around it.” She paused for a moment. “As you may know, I live in New York City. I came up for a few days to see how Aunt Maudie is adjusting to Belle Vista. I’m really very fond of her.” She paused again. “Celia told you that Aunt Maudie’s trunk is missing. Thank you for letting her look for it. It turns out that a cat statue and fancy box are MIA, too.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Aunt Maudie admits she can’t remember moving them, just like the trunk.”

I wasn’t warming to Stacy. She didn’t say that Aunt Maudie reported that the objects were missing or that Aunt Maudie told her about it, or even that Aunt Maudie confided in her. Stacy chose the word admit. It made me feel sorry for Mrs. Wilson, who, it seemed, had been interrogated by her nieces until she confessed.

Stacy laughed. “Of course, she has no memory of not moving them, either. She doesn’t even remember when she saw them last.” Her phone vibrated. She took it from her purse and glanced at the display, then said, “Excuse me a moment.” She stepped aside two paces and turned her back.

“Alyson, how are you?” she asked, her voice suddenly silken. She listened for a moment. “I’m so pleased! Did you decide on the zebrawood or the padauk? . . . Oh, I agree. Zebrawood is perfect . . . Thank you . . . Yes, that’s right…Good…Fine…If you send me the purchase order, I can get the team started right away.”

She finished the call, then turned back to face me, her eyes alight. I sensed she was in her milieu and on her game, and loving every minute of it. I found it hard to respect people who reserved their best behavior for special circumstances like meeting a celebrity or interviewing for a job or, as in Stacy’s case, talking to a customer, but I certainly recognized her look, a private moment of celebration for a hard-won achievement. I felt it every time Prescott’s competed against larger antiques auction houses for an important consignment deal and won.

“Sorry about that,” she said. “I’ve just launched a new furniture line.” “And you just landed a good order!”

“Twenty-seven three-legged oval waterfall tables with tricolored resin for a boutique hotel in Philadelphia.” Her smile broadened. “Needless to say, I’m excited.”

“Tricolor?” I asked, intrigued.

Stacy smiled. “If you ask a new mother about her baby, she’ll show you a thousand photos. This style of table is my baby. May I show you a photo?”

I’d seen river tables, with a central meandering blue or turquoise resin “river” running through the wood surface, and waterfall tables, where the resin “waterfall” runs down a mitered side, but I was unfamiliar with multi-colored resin.

“Sure.”

She brought up a picture on her phone and handed it over.

The photo showed a rosy wood table with a gently curving river that seemed to undulate, and water that seemed to fall over the sides in torrents. The three-dimensional depth was evident.

I looked up and smiled. “It’s magnificent.”

“Thanks.”

“Is that rosewood?”

“Yes, with aqua, royal-blue, and white resin.”

“Most resin tables I’ve seen are one-dimensional. How did you get the effect of the water actually moving and falling?”

“That’s the secret sauce. I invented a new tool—it’s patent pending—that allows the craftsman to generate drapes, folds, and ripples of resin, resulting in a feeling of motion, both in the river and in the waterfall. My favorite part is the white froth.” She smiled with a sassy gleam in her eye. “I offer ten options based on combinations of wood type and resin color. Want to see them all?”

I laughed, my initial negative impression shifting. “Some other time. Do you always use exotic wood?”

“Always and only. That’s another part of the secret sauce. I’m working with a botanist to create a sustainable model—I’ve started a tree farm in Louisiana, just outside of New Orleans.”

“Congratulations. I’m dazzled.”

“Coming from you, that means a lot. Which brings us back to the issue at hand. When it comes to the missing trunk, Celia just rubs her hands together, oh, woe is me. The bottom line is that the ball is in my court and I can’t flinch from what is obviously a difficult duty. You need grit and guts to launch a furniture line, and I’ve got plenty of both, to say nothing of gumption. You’ve started a business, so you know what I’m talking about.”

“I’m sorry,” I interjected, “but I don’t see what—”

“The point is that I’m working on a thousand details at once,” she said, breaking in, “including dealing with a myriad of legal issues. I was on the phone with my attorney today, and I mentioned Aunt Maudie’s forgetfulness, not asking for an opinion even, just chatting. She told me that if you found the trunk or the box and cat, you might have a viable claim. It seems that ‘finders keepers’ is an actual thing.” She smiled, but this time it didn’t reach her eyes. “We’re not looking for trouble, none of us is. All I’m asking for is the truth. If you found them, please tell me.”

“The legal issue isn’t relevant,” I said, trying not to bristle. Stacy didn’t know me, so her suggesting that I might have questionable ethics said more about her than me. “If I found anything, I’d return it.”

Stacy turned toward the street, her hands gripping the railing, a self- anointed savior grappling with defeat. After a moment, she turned back toward me and lifted her chin. “Let me give you my card.” She extracted one from an inside pocket in her purse and handed it over.

Stacy’s company was called Tables by Collins. Positioned just below the name, a tagline read, “Heirloom-quality, one-of-a-kind, custom-created exotic wood and resin tables inspired by nature and crafted in America.” Her showroom was in SoHo, in Manhattan. The off-white cardstock was thick, the lettering engraved.

“If you find anything,” she said, “please call.”

“Good luck with your company.”

She met my eyes, accepting my brush-off with good grace. “Thank you for your time.”

The minute I heard her car engine turn over, I called our locksmith.